In America, everyone is middle class.

And if everyone is middle class, no one is middle class. There is, in fact, no universal definition, so it’s as much defined by education and cultural background as income. But the latter covers such a large swath of Americans who — equally important for would-be members of the middle class — aspire to nicer homes, larger salaries and fancier cars.

Recession — and the fear of recession — is the one thing that could take a wrecking ball to people’s dreams of a middle-class life: steady employment, a vacation or two a year, college education, children in summer camp, and a home that is shiny and big enough to subtly showcase — tactfully and with #gratitude — on social media.

The Pew Research Center uses the middle 20% of Americans’ income and wealth (roughly $106,000) to define that massive club where everyone is hustling for membership. Others say it’s defined as making 50% above or below the median annual income (around $62,000, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and SoFI Learn ).

Many Americans regard a college education as a critical component to becoming middle class. But this alone may not be enough: Outstanding student-loan balances in the U.S. now total around $1.8 trillion, more than any other type of household debt with the exception of mortgages. (And don’t underestimate the earning power of, say, a plumber.)

It has become so amorphous and unattainable that the whole idea of middle class has become meaningless.

Which brings us to homeownership, that other essential marker for middle classdom. Only 66% of Americans, according to some estimates, actually own their own home. To qualify for a home mortgage, with the median price of $418,500, Americans would need to earn $117,000. You can’t be middle class to all people, all the time.

The ability of most Americans to seriously lay claim to the title has become so amorphous and, in many cases, unattainable, that the whole idea of middle class has become meaningless. The middle class is dead. Long live the middle class. Is it possible, given the high bar, that even six-figure households are proudly working class?

In a recent Wall Street Journal commentary titled “Free Trade Didn’t Kill the Middle Class,” Norbert Michel, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives, wrote, “The share of households earning more than $100,000 has tripled over the past five decades.” (And inflation has risen nearly 500% over the same period.)

The debate over whether the middle class has expanded or, in real terms, shrunk, never seems to go away. Do baby boomers or Generation X-ers who started their careers 30 years ago, despite seeing their salaries increase over that time, feel any less worried about retirement or job loss or balancing the household budget?

Don’t mess: Most American weddings are a lot more extravagant than the nuptials of Amazon’s Jeff Bezos

Middle class vs. working class

If we really are all middle class, what does that mean? This was probably the most eye-opening takeaway from this MarketWatch analysis, which laid out which of the five “wealth classes” you likely belong to based on your net worth, according to a category breakdown by Bo Hanson, a financial planner and co-host of the “Money Guy Show.”

People who belong to the “middle class” have a net worth of $29,300 to $209,000 (bad luck if you only have a net worth of $29,200, as you only belong to the “bottom 10%”); the “upper middle class” have a net worth of $209,000 to $714,000; while the “upper class” have a net worth of up to $2.1 million. The “wealthiest 10%” are next.

Some food for thought: Roughly 25 million households in the U.S. earn less than $30,000. For the sake of simplicity, let’s call them “working class” — to employ a British term that seems to be less popular in the U.S. — or blue collar, a more widely used term for lower-paid workers (who work just as hard, if not harder, than everyone else).

Another sign that the middle class has become harder to pin down: The share of U.S. adults living in middle-class households has fallen over the past five decades to 51% in 2023 from 61% in the early 1970s, according to the Pew Research Center, a 10 percentage-point decline over that period. Blame rising inequality.

Trump’s speech to Congress did not mention ‘middle class.’ He mentioned ‘illegal aliens’ five times.

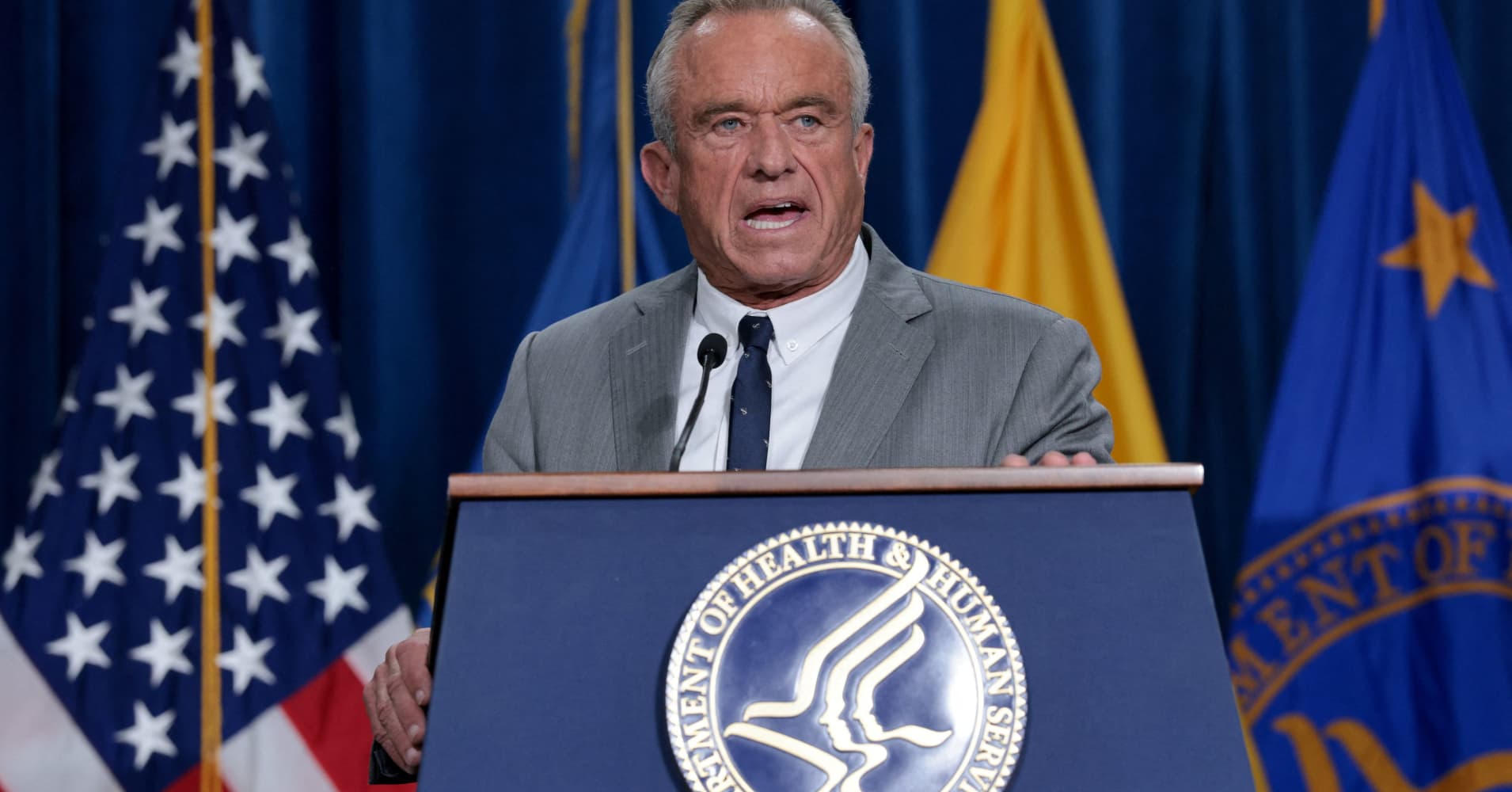

You know who may have noticed this? President Donald Trump. Those figures are broadly, if crudely, reflected in Republican “red” states. Those red states reportedly have a lower median income than blue states and lower levels of education. Red states also have a higher mortality rate, according to this Newsweek analysis of World Population Review data.

American presidents used to appeal directly to the hopes, dreams, aspirations and fears of the middle class. State of the Union addresses often mentioned the middle class, primarily because presidents were aware that folks either wanted to be middle class or thought of themselves as middle class, even if they only had a couple of key qualifiers.

The middle class is not what it used to be, politically speaking at least. They/we used to be red meat for lawmakers. Trump’s speech to the joint session of Congress last March mentioned the middle class zero times. (He did, however, mention the Middle East four times; the only common denominator in that phrase is the word “middle.”)

He dropped the phrase “illegal aliens” five times. Trump, who is a billionaire several times over, did not mention “class” in the context of wealth and social advancement, during his speech. He spoke about the diversity, equity and inclusion contracts at the Department of Education, but not about the educational prospects of voters, per se.

Don’t miss: A warning for all Americans — this is not a good time to put things on credit

The perils of economic mobility

Trump, to be fair, has previously spoken about rescuing the middle class. One theory for such political-stump speeches: People want to better themselves, but it isn’t always as easy as it sounds. Relative economic mobility is lowest for kids who grew up in the Southeast and highest for those who grew up on the West Coast, Great Plains and Northeast.

The president focuses on “why” people may have not attained economic success. While others may disagree, it has been a lightning rod that propelled him to the White House. Former President Joe Biden’s focus on junk fees eating away at the middle class and Kamala Harris’s pleas to broaden the middle class did not resonate in the same way.

That suggests that the financial divide is a cultural one too. Case in point: More than a third of U.S. workers in technology, management, and business and finance occupations belong to the upper-income tier, according to Pew. If you want to find out if your neighbor is a high earner, they probably are if they work in tech.

Still, it’s not all doom and gloom for social mobility and economic equality in America. “Notably, the increase in the share who are upper income was greater than the increase in the share who are lower income,” Pew Research found. “In that sense, these changes are also a sign of economic progress overall.”

Are we doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past and keep spending until another downturn comes along?

“But the middle class has fallen behind on two key counts. The growth in income for the middle class since 1970 has not kept pace with the growth in income for the upper-income tier,” the Washington, D.C.-based think tank added. “And the share of total U.S. household income held by the middle class has plunged.”

And now what? If we’re all middle class or if none of us are really middle class, where does that leave nine-to-five clockwatchers? Are we doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past and keep spending and borrowing until another downturn comes along, and all our middle-class sand castles in the sky are blown away once again?

This time could be different. Middle-class Americans — everyone and no one, baby — could be finally learning their lesson after credit-card debt passed the $1 trillion mark in recent years. We are facing our fears and holding on tight to our dreams. Latest figures have actually shown a decline in credit-card debt for the third straight month.

The barometers of consumer behavior suggest we are not quite sure which way to turn. The savings rate hit 4.5% in June after soaring during the pandemic. Deloitte’s financial well-being index has been on a downward slide since December, and appears to show people have been cutting back on dining out, a favorite middle-class pastime.

Maybe the time has come for Americans to finally embrace our working-class roots.

You can email The Moneyist with any financial and ethical questions at qfottrell@marketwatch.com. The Moneyist regrets he cannot reply to questions individually.

Previous columns from Quentin Fottrell:

What is the worst financial mistake you’ve ever made?

‘I’m confused!’ Why does President Trump want a rate cut so badly?