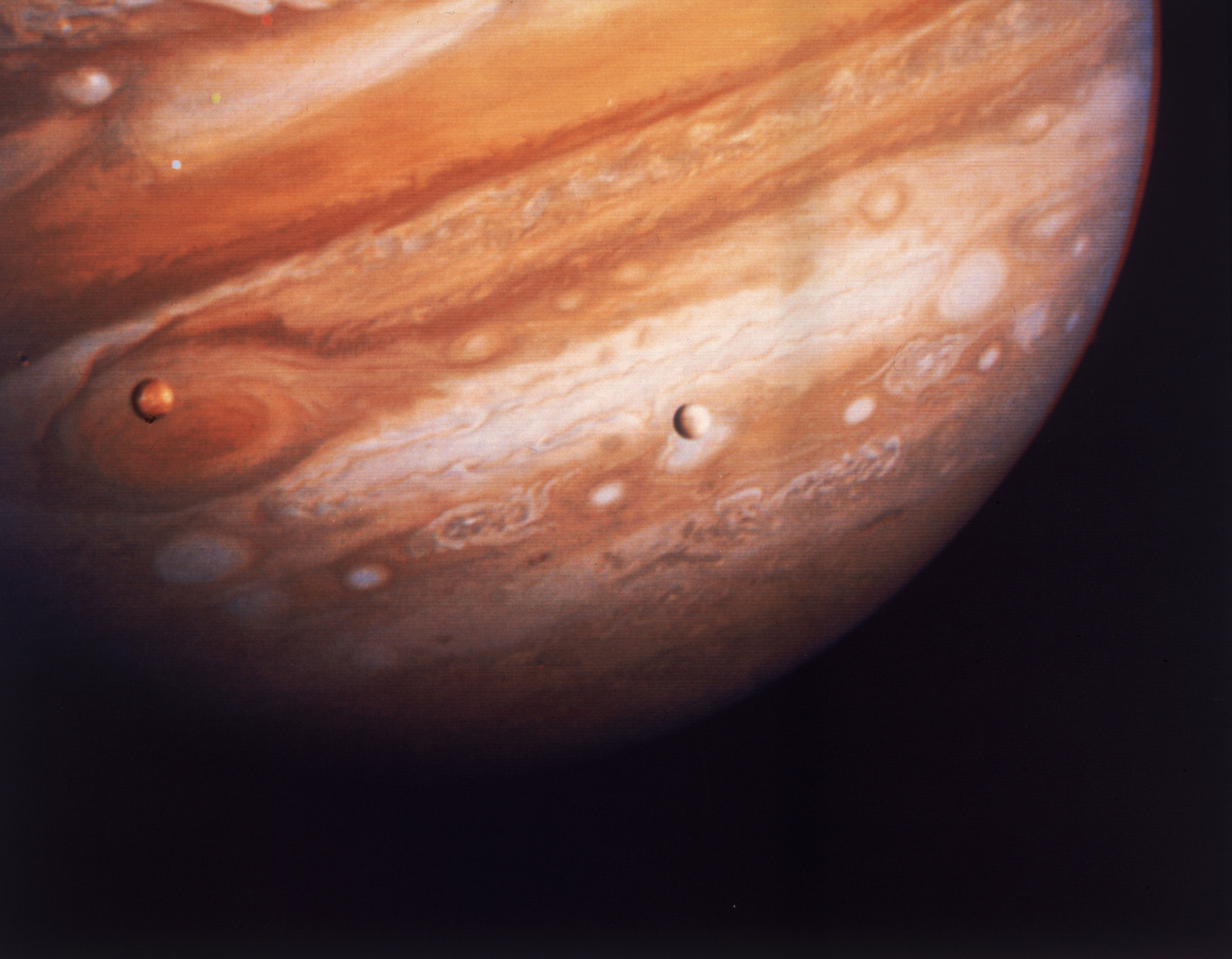

Jupiter and its moons (Image via Getty)

NASA’s Juno spacecraft has discovered that Jupiter is a little smaller than scientists had thought.

The gas giant, known as the largest planet in the solar system, now has slightly smaller measurements at its equator and poles.

This comes from a study published on February 2, 2026, in the journal Nature Astronomy. Scientists explained that Jupiter itself has not changed, but new ways of measuring it are more accurate.

“Textbooks will need to be updated,” said Yohai Kaspi of the Weizmann Institute in Israel.

The experts added that it is not the size of the planet that has changed, but the way scientists measure it.

The new numbers help scientists make better models of Jupiter’s interior and give a clearer understanding of gas giants both in the solar system and around other stars.

More details on Jupiter’s true size as measured by Juno

For decades people have read in textbooks that Jupiter’s equator was 88,846 miles (or 142,984 kilometers), and the poles about 83,082 miles (133,708 kilometers).

Because Jupiter is rotating so fast, it bulges at the equator. But new readings from Juno place the equator at some five miles (eight kilometers shorter) and the poles at 15 miles (24 kilometers) shorter.

It may not be a large number, but it counts when experts are trying to study Jupiter’s atmosphere, internal structure and gravitational field.

Juno has been circling Jupiter since 2016. In 2021, the course was altered so it could make close passes by Jupiter’s largest moons and go behind the planet as viewed from Earth.

These passes let scientists see how radio signals sent from Juno bent as they went through Jupiter’s upper atmosphere or were blocked by the planet.

When the signals came out on the other side, scientists could figure out Jupiter’s size very accurately.

“We tracked how the radio signals bend as they pass through Jupiter's atmosphere, which allowed us to translate this information into detailed maps of Jupiter's temperature and density, producing the clearest picture yet of the giant planet's shape and size,” said Maria Smirnova of the Weizmann Institute, who worked on the data.

Earlier measurements came from only six points collected by NASA’s Pioneer 10 and 11 and Voyager 1 and 2.

Juno added 26 new points, making the measurements much more accurate. Even a few kilometers make a difference.

“These few kilometers matter,” said Eli Galanti, who led the study.

Galanti added:

“Shifting the radius by just a little lets our models of Jupiter's interior fit both the gravity data and atmospheric measurements much better.”

Using the new numbers, models of Jupiter’s interior now match the observations much better.

The research also illustrates why such fine measurements are important. Jupiter is also often used as the yardstick by which to study other gas giants, so an exact measurement of its size could help scientists understand planets elsewhere in the universe.

The new data demonstrates how the planet’s speedy spin influences its shape, and provides fresh information about its atmospheric layers, temperature and density.

Even small variations in the readings could alter how scientists estimate the size of Jupiter’s core, distribution of gas and even magnetic field.

That makes the Juno findings an important step toward not just better understanding Jupiter but similar planets that circle distant stars.

Published on Monday in Nature Astronomy, the results from Juno provide a better understanding of Jupiter and help scientists understand gas giants wherever they are.

Stay tuned for more updates.